Clash on Keefer: The Battle for Vancouver's Chinatown

How’s your memory?

Mine’s selective.

I have weirdly precise memories of 1971, when Ken Dryden made his Montreal Canadiens debut and the Canadiens went on a run, knocking off the dynastic Boston Bruins, the North Stars and the Black Hawks in seven, winning the most exciting Stanley Cup I ever saw.

On the other hand, it was the first one I ever saw. I was nine.

Life seemed unimaginably exciting.

There have been 49 more since, and I hate to say it, but the Stanely Cup just hasn’t been the same since.

THE MEMORY OF CITIES

How about the memory of cities?

That’s another way of asking, to what extent should cities preserve, commemorate and communicate their past - even the bad parts?

After all, city-building isn’t pretty, is it? The history of cities is like an inequality playbook. There’s tenement slums, race riots, systemic discrimination, horrifying labour practices, and every once in a while, like in Winnipeg in 1919, when the people decide they were mad as hell and weren’t going to take it anymore, there were tanks in the streets, shots fired and dead protesters.

These days, a lot of cities have turned into what that white-suit-wearing wit Tom Wolfe once warned Manhattan was about to become back in 1989 in his novel Bonfire of the Vanities: playgrounds for the rich.

The main source of concern these days, as the price points of cities have exploded to beyond affordable for a huge swath of the population is who is going to do all the jobs you need people to do to make a city work?

FIGHT BACK

What’s perhaps new since Tom Wolfe wrote Bonfire is that a lot of other cities have become so-called playgrounds for the rich in the ensuing three decades, none more so than Vancouver, where the last time I looked, a detached home on the east side of the city cost $1.7 million.(CAD). On the west side, it was $3.4 million.

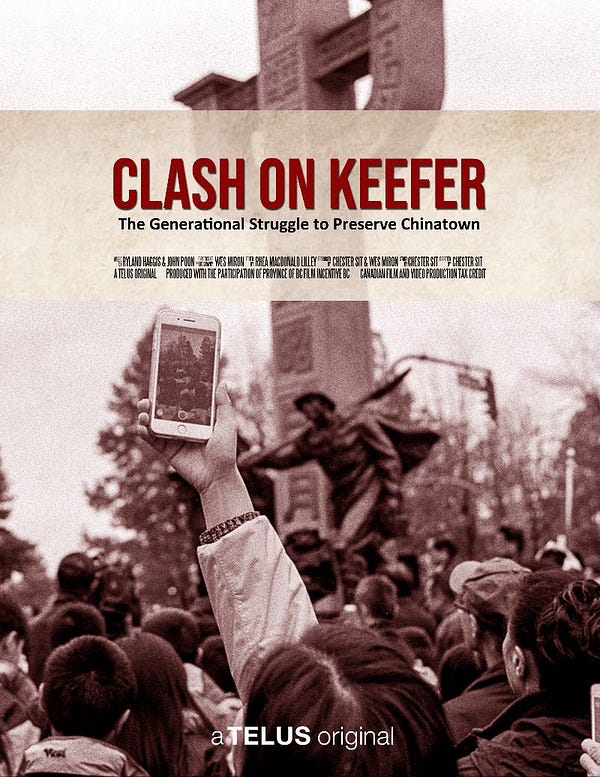

Some of that tension is explored Clash on Keefer, a compelling documentary by Vancouver filmmaker Chester Sit that tells the story behind the community revolt against a proposed condo development at 105 Keefer Street in Vancouver’s Chinatown.

The story of the protest against the condo developers of 105 Keefer isn’t quite a cut-and-dried rally against gentrification, however.

For one thing, 105 Keefer Street is a big empty lot in a struggling neighbourhood adjacent to Vancouver’s East Hastings Street.

It needs to be developed.

But the story that unfolds in Clash on Keefer is one about a tone-deaf development company that did just enough to rally a community to rise up against it in a protest that turned that empty lot into - an empty lot.

In an interview with City Columnist Guy, director Sit said there wasn’t even really a consensus about why the community was against the development.

For some, it was a desire to have affordable housing included in the development that might house some of the aging residents of Chinatown.

For others, it was a desire to preserve the character of a historic neighbourhood.

And for others, it was cool to be against a condo development because - condo development!

“(What the goals were ) really depended up on who you talked to, because there was obviously a desire for social housing, but there was also a desire for cultural significance,” Sit said. “But also how do we keep the cultural flavour of the neighbourhood alive?”

It turns out that empty lot on Keefer Street is no ordinary lot in an extraordinary patch of the most expensive city Canada ever built.

“Not only did the brothers who owned the gas station that used to be there who fought for Canada in the Second World War,” he said, “They were instrumental in getting Chinese Canadians the right to vote - I mean, that’s pretty important!

“It’s a big deal,” he said. “Like, the guys who owned that lot helped get my grandparents the right to vote!”

It turns out Chinese-Canadians weren’t allowed to vote in Canadian elections until 1947.

(I never knew that. How could I never known that? No one talks about it. It’s one of Canada’s dark, dirty secrets. Turns out we have quite a few.)

Sit’s film makes a convincing case that Vancouver’s Chinatown is the site of the origin story of Chinese immigration to Canada.

Clash on Keefer explores the past history of Chinese immigration to Canada in a way that’s compelling, moving - and embarrassing, for anyone who ever wielded their Canadian moral superiority flag on their backpack across Europe, wagging a finger at anyone who mistook them for an American.

(Chinatown arch in Vancouver built for 1901 visit by Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York. By BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives from Canada)

There was the head tax. Chinese-Canadians weren’t allowed to own property anywhere but Chinatown. Chinese-Canadians didn’t have the right to vote until 1947.

Then there’s the Smoked BBQ battle of 1972.

That’s when health inspectors tried to crack down on Chinatown restaurateurs, saying their presentation of smoked barbequed pork didn’t conform to minimum Canadian health standards.

That set off protests in the street that the Chinatown restaurant owners took all the way to Ottawa, arguing that their smoked BBQ pork style was a centuries-old cultural tradition - and they won.

“What I hope the doc shows,” Sit said, “is how racism takes different forms - and it kind of adapts and changes in almost a more benign way as the years pass, right?

“So by the time 70’s, 80’s roll around, it’s like (the Canadian government was saying) ‘no no no! We’re not racist against you! We just think your meat is unclean!’

“Well we’ve literally been doing it this way for centuries if not thousands of years and no one’s gotten sick from it,” he added, “so it’s just really funny how they want to use it as a way to clamp down on Chinatowns.”

There’s the story of community protests that helped to prevent a freeway from being built through Strathcona, Chinatown and other East Van neighbourhoods that protesters said would have destroyed those communities (Strathcona was once a largely-black neighbourhood,where Jimi Hendrix’s grandma lived).

(Although the Georgia Viaduct was built nevertheless, which was almost as destructive as the freeway would have been.)

Clash on Keefer is also a generational story. Chinatown nowadays is mostly home to a few hundred grandparents, not young Chinese-Canadians.

It’s a memory play more than a living neighbourhood. And memory plays are filled with surprise reveals that usually tend to be unpleasant for someone.

Cities everywhere are full of old ghosts that are crumbling, expensive to maintain, drafty and get crappy wifi.

Clash on Keefer tells the story of how a protest movement against a proposal to develop a condominium tower grows into a passionate community of opposition that are concerned about the way Vancouver is being rebuilt, block by block, into a blockbuster city, and along the way erasing memory.

“One other person I talked to and I don’t think it made it into the doc,” Sit said, “said all they (the developers) had to do was put a museum in the lobby of that building and that probably would have gotten enough people supporting you right? Because as we say in the doc, that lot actually has a lot of cultural significance.”

(City Columnist Guy reached out to the developer for comment but hasn’t heard back yet. If we do, we’ll update).

How does it end?

Well, the lot’s still empty. The developer is suing the city. There is litigation over an empty lot in a difficult neighbourhood in a boomtown that isn’t quite sure how much it wants to remember its past.

If that’s a happy or sad ending depends on where you sit in the conversation.

But one thing’s for sure: Clash on Keefer is a thoughtful, compelling meditation on one city’s effort to wrestle between its past and booming present - and full of life lessons for other cities everywhere.